Mark Cole

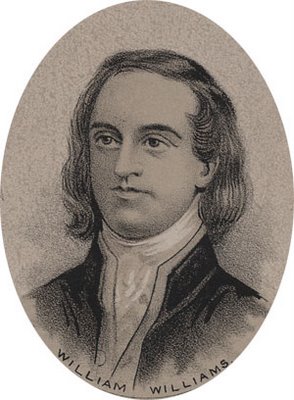

William Williams of Connecticut was the son and grandson of ministers. As such, upon his graduation from Harvard at the age of twenty, Williams began to follow the family tradition by studying theology with his father.But, by 1755, the agitation of the French and Indian War diverted his attention from theology to warfare. Deeply concerned about the French making a proxy war with the British in North America, Williams dutifully enlisted in the fight, and served alongside other colonists on behalf of the British.

During his service, he was under the command of his relative Colonel Ephraim Williams of Massachusetts. Tragically, Colonel Williams was shot in the head and killed in a French ambush during the Battle of Lake George.

The death of Colonel Williams was no small loss to William, or to his fellow soldiers, or to the people of Massachusetts who deeply admired Colonel Williams. Colonel Williams was well-known throughout the colony, and was known to put the welfare of Massachusetts above all else. This held true, even in death: in his will, Colonel Williams bequeathed his estate to support educational endeavors in Massachusetts. Williams College owes its existence to Colonel Williams’ vision, generosity and loyalty to the people of Massachusetts.

The death of Colonel Williams – and the apparent British indifference to it – made a profound impact on young William Williams. By the time his service was complete, Williams had grown to deeply resent the British officers who regarded the colonists (including Colonel Williams) as inferiors, deserving of little honor and no respect.

William Williams never forgot his experience with the ungrateful and haughty British. In time, the desire for independence would come quite naturally for Williams.

When he returned to Connecticut, he never began his theological studies again, but went into business. When Williams was twenty-five, he was elected as the town clerk of Lebanon. He held this office for nearly half a century. He was also elected to serve in the Connecticut Assembly, and he held that seat for some forty-five years. Eventually in 1775, William Williams was selected as a member of the Continental Congress. And in that capacity he signed the Declaration of Independence.

Like many of the other signers, Williams was asked to honor the pledge of his fortune. Without hesitation, in 1779, when most colonists had lost all confidence in the Continental paper money, Williams purchased two thousand dollars’ worth of paper money with hard money, thus propping up the currency and contributing to the financial rescue of the war effort. The costly currency exchange was never spoken of again, and Williams never recovered his financial sacrifice. He kept his word.

In addition, as the town clerk of Lebanon, Williams sustained an ongoing drive for donations to supply the Continental Army with necessities. In this capacity, Williams persuaded many a family to part with their last blanket for the use of soldiers, or to donate the lead weights of their clocks to make bullets for the soldiers to fire from their muskets.

Such were the times during the war for American independence.

Williams survived the war and continued to serve as town clerk of Lebanon and in the Connecticut Assembly until 1804. He died in 1811, at the ripe old age of eighty-one years old.

For more awesome stories about the Signers –

Check out Mark’s book:

Lives, Fortunes, Sacred Honor: The Men Who Signed the Declaration of Independence