Mark Cole

It was once said that Winston Churchill “mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.” The same could be said about Jefferson’s language in the Declaration, not only for its immediate purpose of 1776, but across the centuries. It is simply impossible to overstate the influence of Jefferson’s language and ideals set forth in the Declaration in subsequent American history.

In 1836, a committee of five Texans wrote a Declaration of Independence from Mexico and the language and arguments are virtually a paraphrase of Jefferson’s:

“When a government has ceased to protect the lives, liberty and property of the people, from whom its legitimate powers are derived, and for the advancement of whose happiness it was instituted, and so far from being a guarantee for the enjoyment of those inestimable and inalienable rights, becomes an instrument in the hands of evil rulers for their oppression….”

And after a catalog of abuses of the Mexican government, the Texas delegates declare:

“The necessity of self-preservation, therefore, now decrees our eternal political separation.

We, therefore, the delegates with plenary powers of the people of Texas, in solemn convention assembled, appealing to a candid world for the necessities of our condition, do hereby resolve and declare, that our political connection with the Mexican nation has forever ended, and that the people of Texas do now constitute a free, Sovereign, and independent republic, and are fully invested with all the rights and attributes which properly belong to independent nations; and, conscious of the rectitude of our intentions, we fearlessly and confidently commit the issue to the decision of the Supreme arbiter of the destinies of nations.”

Powerful words, for sure. But not original words.

Some four score and seven years after the Declaration of Independence, President Lincoln would refer to the proposition that our Founding Fathers set forth, namely, that we are a nation “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” Jefferson’s influence on Lincoln’s short speech at Gettysburg was obvious and intentional.

Exactly five score years after Lincoln invoked Jefferson at Gettysburg, Martin Luther King, Jr., did the same on the steps of the Lincoln memorial in Washington, D.C.:

“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.””

The words of the Declaration have thus inspired many over the years– and not just Americans, but liberty-loving people around the globe. And all of this from a document which has no legal force, but just persuasive force. The Declaration, we recall, was not the same thing as the resolution of independence which had been previously adopted by the duly elected members of the Continental Congress.

The Declaration was a moral argument, disguised (barely) as a legal argument, invoking lofty principles that were then and have become since then the goal of all Americans. Today, we may well have legitimate differences as to what equality means and what it requires of us, but, few Americans of whatever political persuasion, religion or background would not eagerly assent to the self-evident truth that all men are created equal.

***

Jefferson’s eloquence as demonstrated in the Declaration cannot be separated from his life of learning as an Enlightenment humanist. As such, Jefferson read, and read, and read. And he collected books.

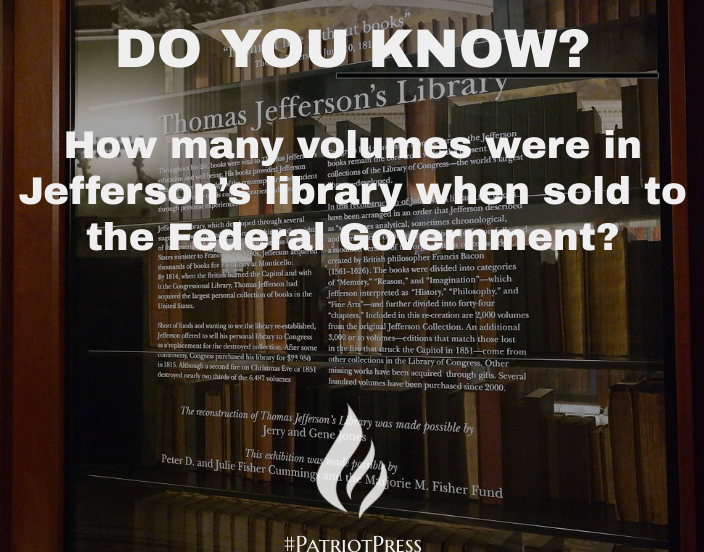

His first library of some 400 books was destroyed in a fire that also destroyed the house in which he was born. That was 1770. His began re-building his collection with a vengeance (keep in mind that he was fairly busy during this time period) and by the time he arrived in Paris as the post-war American ambassador in 1784, he numbered his collection at 2,640 volumes.

During his five-year diplomatic tenure in Paris, he added another 2,000 volumes. When his legal mentor and fellow signer George Wythe died in 1806, Jefferson inherited Wythe’s substantial collection. In Wythe’s will, he commented humbly that while his books were “perhaps not deserving a place in [Thomas Jefferson’s] museum,” they were “the most valuable to him of anything which I have power to bestow.”

Thus, with the generous bequest from Wythe, Jefferson’s library grew yet again. Then, in 1814 after the invading British army burned the Capitol building and destroyed the congressional library, Jefferson offered his library to the nation. Not for free, of course, but nonetheless, an offer was made by Jefferson to the United States to allow the nation to purchase immediately what he had meticulously built for more than thirty years.

An appraiser was found to value and catalog the books. The number of volumes totaled 6,487. The price was to be $23,950, a very substantial sum which would assist the debt-ridden Jefferson tremendously. Predictably enough, Federalist opponents howled in protest. One Cyrus King led the charge, arguing that the purchase of the library would disseminate Jefferson’s “infidel philosophy” throughout the land. For good measure, he added that Jefferson’s volumes were “good, bad, and indifferent, old, new, and worthless, in languages which many can not read, and most ought not.”

King’s tirade, eerily reminiscent of the election of 1800, failed to scuttle the deal and the sale went through. The ten wagons with the new Library of Congress left Monticello for Washington in April of 1814. Many of these volumes are available today for appropriately credentialed scholars.

But, true to his modus operandi, Jefferson did not allow his shelves at Monticello to lay bare for long. From April 1814, until his death on July 4, 1826, Jefferson built up his final personal library, finishing with a formidable 1,600 volumes.

***

President Franklin D. Roosevelt once wrote, more

“than any historic home in America, Monticello speaks to me as an expression of the personality of its builder. In the design, not of the whole alone, but of every room, of every part of every room, in the very furnishings which Jefferson devised on his own drawing board and in his own workshop, there speaks ready capacity for detail and, above all, creative genius.”

Jefferson finally began to truly enjoy Monticello shortly after he left the Presidency in the spring of 1809. He was, indeed, the architect of the home – a project he had been working on for literally forty years (the final touches taking more than ten years to complete). But he was more than the designer. The project was an embodiment of who Jefferson was, as a statesman, an Enlightenment humanist, an inventor and a thinker and reader with a breadth of interests that is probably greater than any American who has ever lived. Indeed, so personal was Monticello to Jefferson that he referred to it, interestingly, as his “essay in architecture.”

The house reflects Jefferson’s strict application of classical forms – and in true Enlightenment fashion, a rejection of the architectural traditions then rooted in Virginia.

When Monticello was complete, it was, quite simply, like no other home in America. It had the first dome of any home in America. It features octagonal rooms, small private staircases, numerous elliptical arches connecting rooms, interesting bed alcoves, a greenhouse and aviary, varying ceiling heights, a closet reached only by a ladder, an entrance hall that served as a museum of Jefferson’s artifacts and relics, and countless other oddities and details – each of which spoke of Jefferson. As such, Monticello, like its creator, remains a national treasure.

Get the entire Thomas Jefferson story, and so much more –

Check out Mark’s book:

Lives, Fortunes, Sacred Honor: The Men Who Signed the Declaration of Independence