Mark Cole

Jefferson entered the bar in 1767 and by the early 1770’s, he had already been elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses. In 1774, he wrote A Summary View of the Rights of British America and meticulously laid out his case that the historic rights of the American colonists were being lawlessly usurped by the Crown.

The Summary is a remarkable piece of advocacy by the 31-year old Jefferson. Still today, his legal training and historical knowledge leap off the page. And his prose is clearly getting warmed up for the Declaration, still two years off.

The Summary directly addresses King George, accusing him of:

“many unwarrantable encroachments and usurpations, attempted to be made by the legislature of one part of the empire, upon those rights which God and the laws have given equally and independently to all.”

And more:

“That these are our grievances which we have thus laid before his majesty, with that freedom of language and sentiment which becomes a free people claiming their rights, as derived from the laws of nature, and not as the gift of their chief magistrate ….[K]ings are the servants, not the proprietors of the people. Open your breast, sire, to liberal and expanded thought. Let not the name of George the third be a blot in the page of history….

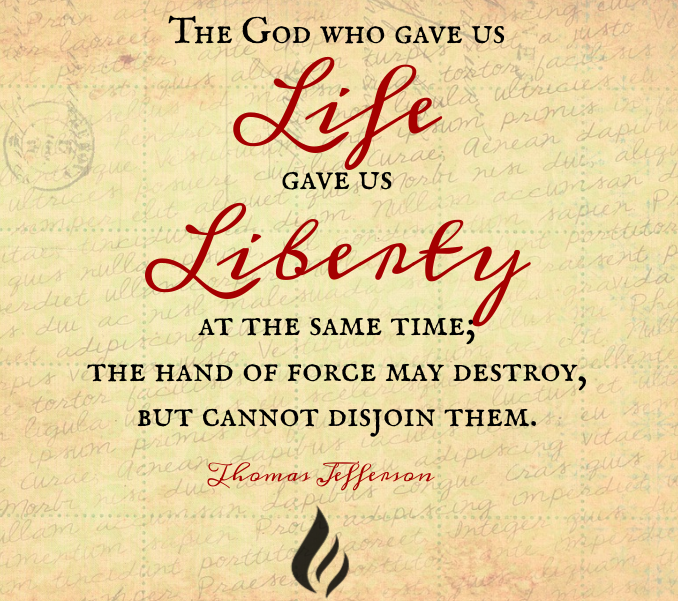

The whole art of government consists in the art of being honest. Only aim to do your duty, and mankind will give you credit where you fail. No longer persevere in sacrificing the rights of one part of the empire to the inordinate desires of another; but deal out to all equal and impartial right….The God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time; the hand of force may destroy, but cannot disjoin them.”

Jefferson grounded his crystal-clear case deeply in British history and the common law, arguing simply that the rights of the colonists are God-given and cannot be taken away by a lawless sovereign. Moreover, the American colonists’ rights are no different from the rights of other citizens whether they reside in England, or elsewhere in the empire.

Finally, the duty of the Crown is to recognize and protect those rights. This same line of reasoning would be employed a mere two years later in the Declaration of Independence.

King George could never say that Thomas Jefferson failed to give him a fair warning!

Following publication of the Summary, Jefferson was recognized throughout the colonies as a brilliant advocate for the rights of the colonists. He began to move to the forefront of the independence movement. Clearly, the years of hard work with Wythe had paid off.

Obviously Jefferson’s Summary was not as well-received by the Crown, or its local officials.

Lord Dunmore, the British colonial governor in Virginia, was so exasperated with Jefferson’s broadside that he threatened to have the author arrested for high treason. Jefferson was not arrested, but it would not be the last time that his writings would be labeled as treasonous by the Crown: in A Summary View, Jefferson aimed at his target and in the Declaration of Independence, he pulled the trigger.

The Declaration of Independence

In June of 1776, Richard Henry Lee introduced his resolution for independence in the Second Continental Congress. When it became clear that Lee’s resolution had the momentum, the members of Congress appointed a committee of five to draft a public communication of what the resolution was soon to accomplish.

The members of that committee were Thomas Jefferson, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingstone, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams.

It was determined that Jefferson should be the primary author and his first draft was submitted to Adams and Franklin privately. The two statesmen-scholars suggested revisions and Jefferson worked up a second draft to present to the full committee of five.

(The version that Adams and Franklin revised is housed today at the Library of Congress).

The committee then adopted that version and it was sent to the Continental Congress on July 1. Speeches were given, and a few minor revisions were made.

On the morning of July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress approved the Declaration of Independence.

Church bells rang throughout Philadelphia announcing America’s first Independence Day.

A Philadelphia printer named John Dunlap was immediately commissioned to print a few dozen copies of the Declaration. (Two of these – including George Washington’s personal copy – are housed today in the Library of Congress).

On July 5, the President of the Continental Congress, John Hancock, dispatched Dunlap’s prints to the legislatures of New Jersey and Delaware. On the 6th, the Pennsylvania Evening Post printed the first newspaper version of the Declaration.

On the 8th, the Declaration was read in public for the first time, followed by a reading on the 9th to the Continental Army in New York – ordered by Washington himself.

Finally, on July 19, the Continental Congress resolved that the members should physically sign the Declaration. That process began on August 2. It is this 24 x 29 parchment, signed by 56 patriots, which is displayed today in the National Archives and viewed by thousands every year.

Get the entire Thomas Jefferson story, and so much more –

Check out Mark’s book:

Lives, Fortunes, Sacred Honor: The Men Who Signed the Declaration of Independence