“I must be independent as long as I live,” John Adams once said. And so it all began, the life of this incredible man: lawyer, patriot, diplomat, President, husband and father – and above all else, a man of independence.

His father was a minister and naturally enough was eager for his son to follow in his footsteps. But what Adams as a boy really wanted to do was to become – gasp! – a farmer.

Horrified by this presumptive career choice, Reverend Adams organized a demonstration day of sorts where they would work together for a day, father and son, in the fields under the burning sun, just like farmers. He would show young John what the life of the farmer entailed, day in and day out. Surely that would break the young boy of his belief that the life of the farmer is a good one. Or so he thought.

The day was long and the work was hard. Reverend Adams toiled and sweated. In secret delight, the boy struggled to keep up the pace with his father.

Later, in the debriefing over dinner, a famished, aching and sun-scorched Reverend Adams confidently asked John, “Well, John, are you satisfied with being a farmer?”

“Yes, sir, I like it very much,” the boy proudly answered.

His father’s attempt to straighten out his thinking about farming having failed, John was sent back to the Latin school.

Independence forever.

Institutional school and the conformity it required was never John Adams’ strong suit. He found the teachers pedantic, boring and slow. The young Adams was either way behind, or, when the inclination took hold, as it often did with mathematics, he would dash ahead and do the exercises for the entire book while the rest of the class plodded along together at a more leisurely pace.

Independence forever.

Out of desperation, his father sent John to study one-on-one with a local scholar, Joseph Marsh. Marsh reported back that John had an exceptionally keen mind – though he also reported to Reverend Adams that he was, according to Adams biographer Page Smith:

“…a curious combination of traits – sober and reserved, passionate and intense, stiff and shy yet affectionate and responsive; impulsive, headstrong, sharp-tongued, with an aggressive self-assurance….”

Rarely has a more accurate description of a human being been set forth. Impulsive? Headstrong? Aggressively self-assured?

Independence forever.

As time went on, John Adams lost his exclusive fondness for farming, developed a passion for intellectual pursuits (at least those which interested him), and, no doubt to the relief of his father, attended Harvard and then settled on a legal career.

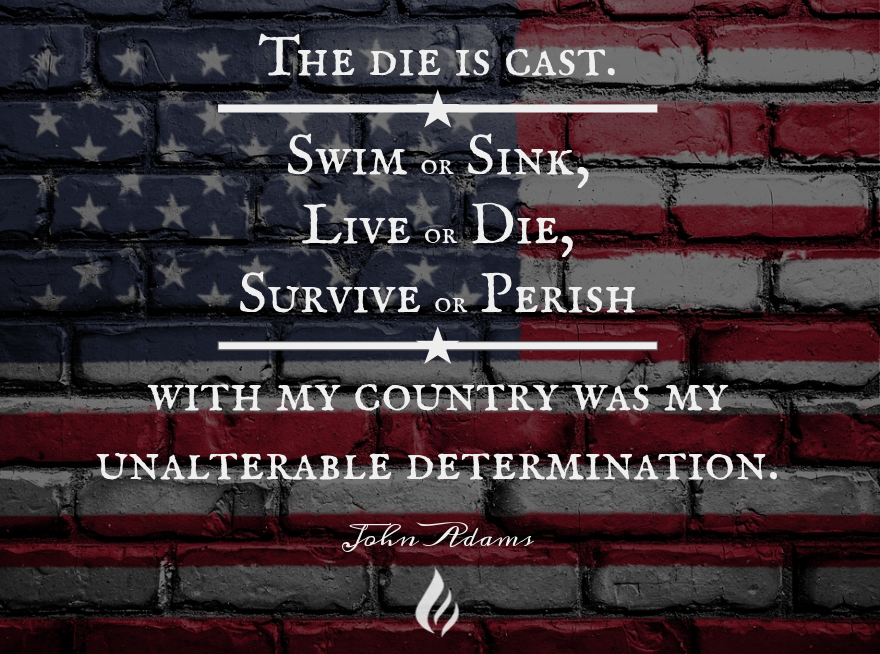

His legal skills rapidly led him to become the most prominent attorney in Boston. It was not long before he took up the cause of American independence, linking arms with his cousin Sam Adams and fellow Bostonian John Hancock. In the aftermath of the Boston Tea Party he wrote, “The die is cast. Swim or sink, live or die, survive or perish with my country was my unalterable determination.”

Independence forever.

At the age of 38, Adams was elected to the Continental Congress as a resolute and steadfast proponent of independence. He forcefully advocated the patriot position every chance he got. But he was more, much more, than just an orator. John Adams was a tireless worker. Eventually he served on some fifty committees, chairing half of them. His legendary work ethic earned him nickname “The Atlas of Independence” as so much of the movement was on his shoulders.

In 1776, the time had arrived. Continental Congressman Adams chaired a special committee charged with the duty of crafting a declaration of independence. The others on the committee were Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingstone, Roger Sherman, and of course, Thomas Jefferson. Franklin was in less than perfect health, so he could not do the actual writing. So, upon Adams’ insistence, Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration.

When the document was ready to present to the Continental Congress, Adams capably defended it with his superb oratory. A few minor revisions were made by the whole Congress and the Declaration was approved on July 4, 1776. Each of the committee members, together with 51 other men, signed the Declaration of Independence and openly pledged their lives, fortune and sacred honor for the cause.

Independence forever.

John Adams was often right about things. But he was convinced he was always right. And he simply would not compromise with or tolerate those who disagreed with him when he was in this mode, even referring to other men as “fools” right to their faces.

For Adams, this quality – what we might call stubbornness – was an important moral virtue. For him, tenacity and inflexibility were better understood as honor. “I would quarrel with every individual before I would prostitute my pen,” he once wrote. “I am determined to preserve my independence, even at the expense of my ambition,” he once said.

It’s a good thing that he felt that way, because that is ultimately what happened.

Independence forever.

In the war-torn decade following the Declaration, Adams was the top American diplomat throughout Europe. Accompanied by his son, John Quincy, John Adams pressed the cause of independence tirelessly. The Treaty of Paris, ending the American war for independence, is one of his greatest contributions to the founding of America.

Lesser men would have sought peace too rapidly and failed to secure the necessary guarantees of independence from the crown. Adams proved to be a tough negotiator and shrewd diplomatic tactician right up to the finish line.

Independence forever.

When he returned home, his country elected him to the Vice-Presidency under the Father of America, George Washington. “My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever man contrived,” was how Adams aptly described his position.

Eight years later, John Adams won the Presidency himself, but unlike Washington before him and Jefferson after him, Adams failed to win a second term. His politically fatal defect? He stood alone too often. Though he was certainly a man of the Federalist Party, he sought to avoid party ties and in so doing failed to maintain his allies. Simultaneously, he alienated himself from the opposition party. He became a party of one. And he was not re-elected. (The second man in American history to claim the dubious distinction of failing to win re-election would be his son, John Quincy Adams).

Independence forever.

In their amazing and intertwined lives, Jefferson and Adams first admired each other; then they hated each other. They were originally allies, but later they became vicious enemies. Their lifetime was characterized early on by productive collaboration but then later by intense rivalry and backstabbing.

At the low point in their relationship, it is hauntingly conceivable that Adams and Jefferson could have been the ones to fight a duel, rather than Burr and Hamilton.

Even so, through it all, Jefferson kept a bust of Adams in his parlor at Monticello. Perhaps it was Jefferson who never gave up hope for reconciliation? After all, the two giants of independence had struggled against the odds – together – in 1776. They had worked beyond political and personal differences to serve together in the Washington administration – the first (and last) non-partisan administration in American history.

But when Adams became President and Jefferson became Vice President – an arrangement which preceded Adams’ downfall – Adams, rightly or wrongly, believed that Jefferson was responsible for every bit of misfortune and failure that his administration encountered. Accordingly, when Jefferson was elected in 1800 and Adams was booted out of office, Adams famously refused to attend Jefferson’s inauguration (the vanquished John Quincy Adams, would likewise refused to attend the swearing in of his successor, Andrew Jackson).

Independence forever.

On New Year’s Day in 1812, several years after Jefferson had finished his second term, it was Adams who wrote Jefferson a letter, thus ending the steely silence of more than a decade. Over the next 14 years, they would write more than 150 letters to each other.

Through this correspondence, the friendship of 1776 would be miraculously restored.

Finally, in 1826, in one of those strange facts of history which would be unbelievable if passed on to us in the form of fiction, Adams and Jefferson died within hours of each other on July 4th, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

There are conflicting accounts of what Adams’ final words were. One says, I think implausibly, that he uttered, “at least Jefferson still lives” – the irony being that Jefferson had died a few hours earlier.

The account which I think contains more truth in it says that Adams’ parting words were:

“Independence Forever!

Want more awesome history on the Founding Fathers?

Check out Mark’s book:

Lives, Fortunes, Sacred Honor: The Men Who Signed the Declaration of Independence